The Global Task Force for Cholera Control has recently established a strategy to put an end to cholera epidemics in up to 20 countries and reduce cholera-related deaths by 90% by the year 2030(1). The multisectoral approach involves early detection and quick response to contain outbreaks. However, rapid control of cholera outbreaks in urban settings can be a major challenge, due to the potentially explosive nature of cholera in crowded settings(2,3).

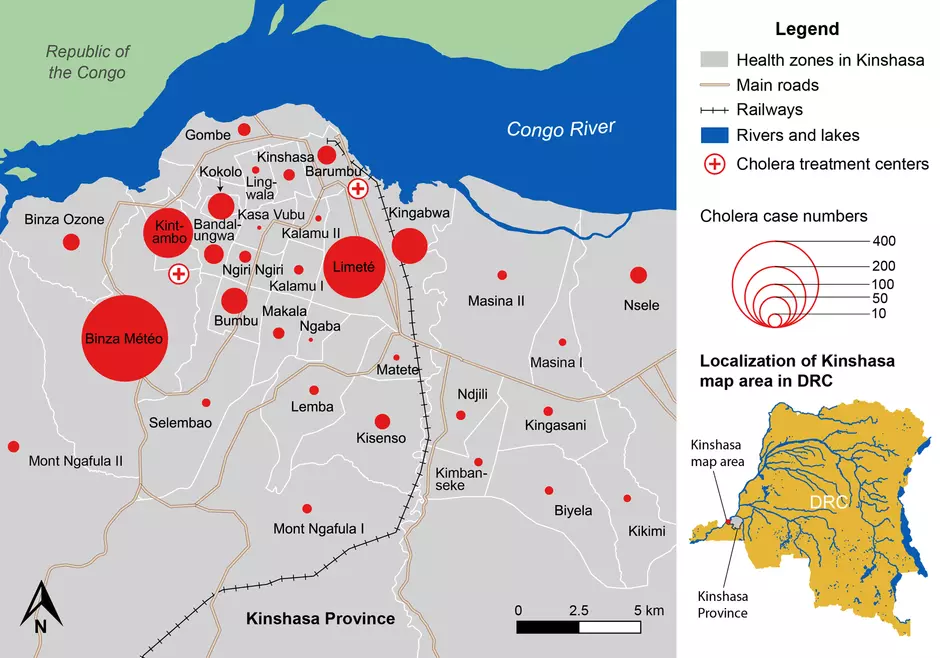

In 2017, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) experienced the largest cholera epidemic to affect the country since 1994, with approximately 56,000 cholera cases reported nationwide(4). Late in 2017, Kinshasa, the capital of the DRC, experienced a cholera outbreak that showed potential to spread throughout the city.

In a recent publication in BMC Infectious Diseases, Bompangue and colleagues describe a novel targeted water and hygiene response strategy implemented to quickly stem the outbreak(5). To contain the outbreak, water supply and hygiene response interventions targeted case households, nearby neighbors and public areas in case clusters. Intervention delivery was organized by sub-dividing each cluster into a grid. Household level interventions focused on household water treatment and safe storage, home disinfection and hygiene promotion. Interventions in public places included installation of water bladders, water chlorination points, handwashing points, and health promotion campaigns(5).

From January 2017 to November 2018, a total of 1,712 suspected cholera cases were reported in Kinshasa. In a preliminary community trial, the study found that following implementation of the response, the outbreak in Kinshasa was quickly brought under control. The weekly cholera case numbers in the most affected health zones - Binza Météo, Kintambo and Limeté - decreased by an average of 57% after two weeks and 86% after four weeks. The total weekly case numbers throughout Kinshasa Province decreased by 71% four weeks after the peak of the outbreak(5).

This successful strategy builds upon previous studies that have shown the increased risk of cholera infection for household contacts of cholera patients(6) and among nearby neighbors of cholera cases(7).

As cholera outbreaks that expand in urban areas often eventually spread to nearby at-risk areas(8-10), effective strategies to control outbreaks in urban settings may play a major role in the control and prevention of the disease on a local, national and regional level. To stop cholera transmission in other vulnerable cities and reduce outbreak expansion, the strategy described by Bompangue and colleagues may be adapted and implemented in other urban settings.

References:

1. GTFCC. Declaration to Ending Cholera [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/cholera/task_force/declaration-ending-cholera.pdf?ua=1

2. Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK. Cholera. 2004;363:223–33.

3. World Health Organisation. Prevention and control of cholera outbreaks: WHO policy and recommendations [Internet]. 2018. Available from: http://www.who.int/cholera/prevention_control/en/

4. World Health Organization. Cholera case and death numbers by country [Internet]. The Weekly Epidemiological Record. Available from: https://www.who.int/wer/en/

5. Bompangue D, Moore S, Taty N, Impouma B, Sudre B, Manda R, et al. Description of the targeted water supply and hygiene response strategy implemented during the cholera outbreak of 2017-2018 in Kinshasa, DRC. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(226):1–12.

6. Kone-Coulibaly A, Tshimanga M, Shambira G, Gombe N, Chadambuka A, Chonzi P, et al. Risk factors associated with cholera in Harare City, Zimbabwe, 2008. East Afr J Public Heal. 2010;7(4):311–7.

7. Azman A, Alcalde FJL, Salje H, Naibei N, Adalbert N, Ali M, et al. Micro-hotspots of Risk in Urban Cholera Epidemics. bioRxiv. 2018 Jan;248476.

8. Rebaudet S, Mengel MA, Koivogui L, Moore S, Mutreja A, Kande Y, et al. Deciphering the Origin of the 2012 Cholera Epidemic in Guinea by Integrating Epidemiological and Molecular Analyses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(6):e2898.

9. Moore S, Dongdem AZ, Opare D, Cottavoz P, Fookes M, Sadji AY, et al. Dynamics of cholera epidemics from Benin to Mauritania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(4):1–16.

10. WHO. Somalia Emergency Weekly Health Update (May 5-11, 2012). 2012.